Guest Post: Helping K-12 Students Make Better Choices

The authors have combined their expertise in the fields of education and decision science to establish Decision Education instruction for students in the Delta School District in Vancouver, British Columbia.

At the start of each year, elementary school teachers everywhere are faced with a dilemma: what seating arrangement will work best for their 20-30 students? Sitting by the window encourages day dreaming; sitting with friends reinforces cliques; sitting at the back of the room reduces participation. How should this choice be made?

One creative teacher in British Columbia asked her Grade 6 students to play a simple game. First they were asked to make a note of where they wanted to sit and with whom. Then, working individually, students thought about about 3 or 4 reasons why seating options might matter: did they want to see the blackboard clearly, or sit with friends, or avoid someone they disliked? After writing down what mattered to them the class, working together and led by the teacher, was asked to evaluate different seating options in terms of their expressed criteria. To make the choice more realistic and fun, each student ranked several seating options in two ways: how did they feel about it (the initial evaluation, using their hearts and emotions) as compared to what did they think about it (using their heads and evaluative criteria). This values-based focus led into a discussion about what to do when your head and your guts are not in alignment. Sound interesting? The students thought so: this simple one-hour exercise kept them engaged and talking together for several class periods, and it worked so well that subsequent classroom discussions often introduce issues in these same terms: what’s the problem, what matters to my head and heart, what are the alternatives, and what are the key trade-offs?

Without knowing it, these students are being exposed to the building blocks of good decision making. Making choices—beyond simply assigning seats — is fundamental to leading a happy, healthy, and productive life. It’s also fundamental to becoming a good citizen, starting with the ability to think through questions as simple (in some ways) as what bike or car should I purchase to summer job options to questions as complex (in some ways) as what candidate do I vote for and do I support stronger controls on gun sales or higher carbon taxes? Basic decision-making skills are essential learning for youth today: no matter how proficient students are in academics, arts, or sports, they are unlikely to lead a contented life or contribute meaningfully to society if they lack the ability to make good decisions.

Most state and provincial education ministries recognize this and emphasize high-level decision-making skills such as critical reasoning or creative problem solving. Yet the mandated curriculum stops short of explaining how to teach these core competencies; this is left to the discretion of classroom teachers, who recognize the importance of making good choices but typically lack knowledge of effective decision-making practices and access to classroom-ready materials. As a result, little classroom time is currently spent helping students identify and learn how to carry out the required elements of decision-making.

In recent years, books on decision making (e.g. Thinking, Fast and Slow by Nobel winner Daniel Kahneman) have become best sellers. Innovative teachers may be curious about how to incorporate this literature into their classrooms but not know where to start in teaching the types of thinking and methods that go into making sound individual or collaborative decisions. This is evident so far in our work in British Columbia. With few exceptions, teachers tend to move immediately to inviting students to vote on a series of options that come to mind. Moving straight to the voting process skips key elements of good judgment and decision making such as identifying values and perspectives, developing creative alternatives to achieve these values, gathering reliable information about the likely consequences, and talking with others to understand their differing perspectives.

In addition to the many tough personal choices they face, most students today are keen to engage in the world in positive ways. Through the application of basic decision skills to everyday choices, students can begin to build the habits and skills needed to move from “me” to “we” and to engage collaboratively in civil society. The fast-paced nature of modern society increases the pressure to make snap decisions and judgments and opens students up to a range of common decision traps and biases that include ignoring key considerations, given insufficient attention to the relevance of information, or avoiding difficult trade-offs. As one result, the nature of public discourse has become increasingly polarized – a lament that is often heard but rarely linked to the absence of formal listening skills learned as part of collective decision making.

Who is to blame? Not teachers, who everywhere are grappling with the shift from a content- based curriculum to a skills-based curriculum by searching for classroom-ready materials in public spaces such as TeachersPayTeachers, Twitter, blogs, and conferences. Not students, who learn all about the importance of STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) but often hear nothing about findings from the “decision sciences” that examine how people do and should make decisions. And not parents, who worry every day about the difficult choices their kids will have to make (drugs, sex, college). In our view, learning something so basic as making good choices is a collective responsibility: the science and art of making good decisions remain (for most individuals and families) well off the radar, and as a result the recognition that a small set of common-sense, user-friendly skills could lead to greatly improved personal and societal choices has rarely been articulated.

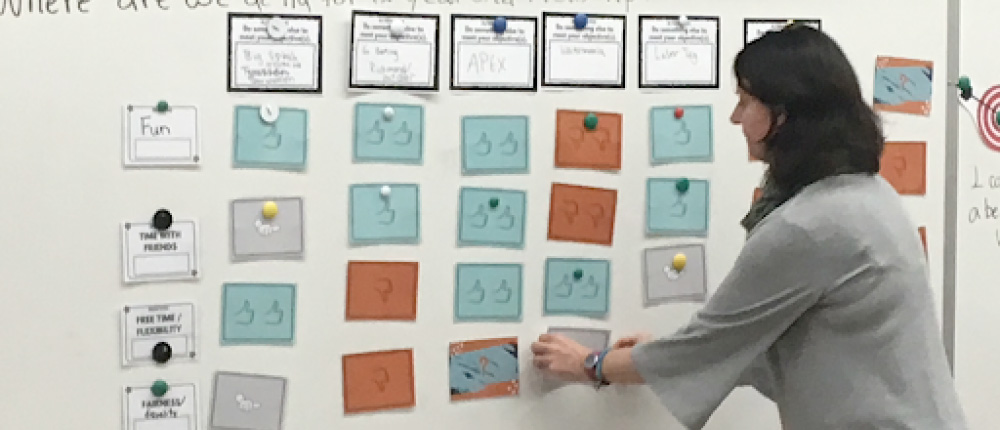

With the support of leadership and teachers from the Delta School District (a suburb of Vancouver, British Columbia), we are exploring possibilities for systemic changes in students’ individual and collective choice-making skills. A first step has been to design half-day decision- skills learning opportunities for leaders and K-12 teachers. Working in facilitated small groups, teachers develop grade-specific curricula to help students learn better decision-making procedures in the context of topics such as choosing healthy foods, assessing local infrastructure options, donating to humanitarian charities, or identifying community actions to address climate change. In classrooms where these strategies and tools have been used, surveys (of teachers and students) confirm that students’ level of discourse and sophistication in decision-making have improved along with their skills in making better choices as part of a group.

An important long-term goal of this project is to increase the quality of discourse about divisive issues in society while increasing students’ confidence that they can handle a range of decision- making opportunities. Students who were taught to employ value-focused thinking as a way of dealing with tough problems are able to learn tools that help identify not only their own concerns but also what matters to others whose circumstances or history are different. This helps to move students (and perhaps also their families) from inflexible debates to flexible dialogue, with the goal of resolving conflicts and finding mutually acceptable solutions. We see great potential in using decision skills as a framework for structuring inquiry and enhancing students’ critical and creative thinking capabilities. How would our future world change if youth were better prepared to address the tough personal and social choices they inevitably will face? Take a minute or two and think about it…